Saltonstall Salon

Today, I attended the second installment of the Saltonstall Foundation's new Art Salon series, which takes place at the Museum of the Earth, a natural history collection. The striking, angular building, filled with fossils and artwork depicting long extinct lifeforms, was a fun and offbeat locale for discussions of contemporary artists and their work. I got there early, so I got a chance to wander the museum, which I hadn't been able to do at the first Salon. The recently discovered Hyde Park Mastodon, almost (95%) complete, was impressive. (If you want to, you can sponsor one of the bones.)

Today, I attended the second installment of the Saltonstall Foundation's new Art Salon series, which takes place at the Museum of the Earth, a natural history collection. The striking, angular building, filled with fossils and artwork depicting long extinct lifeforms, was a fun and offbeat locale for discussions of contemporary artists and their work. I got there early, so I got a chance to wander the museum, which I hadn't been able to do at the first Salon. The recently discovered Hyde Park Mastodon, almost (95%) complete, was impressive. (If you want to, you can sponsor one of the bones.)There was light food, coffee and tea, set up by the catering people. I'm not sure what the numbers were, but I think that there were substantially fewer visitors than last time. Perhaps the weather, which was cold and windy? There were four speakers; each was supposed to talk for ten minutes, although this wasn't rigorously enforced. Many of them were quite awkward as public speakers, which seems to be the case with many visual artists (and something that I certainly identify with myself). Each artist was introduced by Laurel Guy, director of the Foundation. All brought samples of their work, and stayed around after the formal talks to chat with visitors.

First to speak was Virginia Cobey, who showed landscape paintings, as well as "abstracts". (This latter usage is probably out of date, and I have to say that I find it awkward.) She described her working schedule: plein-air landscapes when it is warm out, abstractions in her studio during the wintertime. Her emphasis was on the formal aspects of her work: selecting a composition from nature, building contrasts of shape and tone, establishing unity, and so forth. Much of this seemed generic (not particularly specific to her own work), and the talk was for the most part pretty dry.

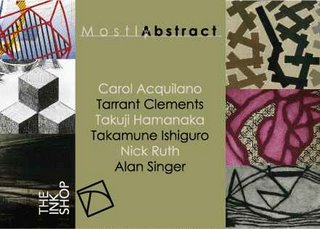

Craig Mains, my favorite artist of the group, spoke next. Mains had a solo exhibit of his work at the Ink Shop last fall, and another one at Gimme Coffee earlier this year (an show from 2004 is reviewed colorfully here). Particularly nervous, he warned the crowd that he might suddenly stop talking (which luckily didn't happen).

First, he discussed his symbolic approach, which incorporates icons of disaster and flux (or icons in flux). Houses, trailers, ice-cream trucks, telephone poles, trees, Cessnas, helicopters, and more suffer the ravages of wind, fire and flooding. He noted the human attraction to such chaos and destruction, which he wants to separate from the human tragedy that usually accompanies it in the real world.

He also discussed his technical process, which has unusual aspects. He applys wet media (usually watercolor) to porous acetate sheets, which he can run through a printing press. Often, he cuts his iconic forms out, arranging and rearranging them. Although the monotype process is meant to produce a singular, unique image, Mains reuses these cutouts in further images, in which they grow progressively fainter as the pigment fades. Images and their "ghosts" are used to form series. He also talked about his use of Internet search engines as a source of imagery, which sometimes produces unexpected but useful juxtapositionsfor example, a search for "high tension wires" producing an image of a downed helicopter.

Bill Roberts, who teaches at Wells College, talked after Mains. He spoke engagingly about his life history, but didn't have too much to say about his current painting, a series of "shaped" (non-rectangular) pieces inspired by Elizabeth Murray's work. These pieces, done mostly in pinks, blues and whites reference the notorious "dimpled chads" from the 2000 election, which seemed like a pretty forced attempt at humor. Some of his earlier work, reproduced in catalogs he was giving away, looked more interesting. He also spoke about his work as a sports photographer (football and horse racing), and his love of Spain and its culture and art.

His philosophy of teaching was presented as a series of cliches, likely familiar to anyone who has attended art school: be spontaneous, experiment, be willing to fail, value the process of making art over the results, be fufilled in life. (He reminds me of a particular teacher I had in art school about whom I have very mixed feelings.) I don't know if Roberts is a good teacher or not, but I personally don't find these truisms very useful or encouraging.

Linda Swanson, a ceramic artist currently attending grad school at Alfred University, was the last to get up. Her work, inspired by the landscape of Iceland, uses natural processes such as dripping, cracking, and the formation of crystals, which act in unanticipated ways. Unlike the other artists, she read from notes for much of her talk, which gave it an strangely academic tone, seemingly out of place. She spoke of an interest in referencing the geological and the biological, different scales, mapping the landscape. The difference between science and art is important for her; the latter allows for things to be "other than what they are", which is a nice way of putting it.

Swanson showed two circular porcelain pieces, meant to be hung on a wall, although they were shown on a table instead (due to a lack of set-up time). The pieces were coated in thick layers of glaze, which were deliberately allowed to crack. One was white, black, and red, and the other (my favorite of the two) a pond-like green, with white crystal growths. The pieces receded behind their metal frames.

The quality of both the artists' talks and their work (which seem to correlate), was more uneven than at the first Salon, which is too bad. Still, it was an enjoyable event. I'm looking forward to the next one, which takes place on March 26.

Labels: craig mains, ithaca